My brother told me there were ghosts upstairs—ghosts of old and ugly people who thought this was still a hotel. He said they roamed the halls all day and all night, looking for the bathroom.

I wasn’t quite old enough to know better, and I had an overactive imagination, so it’s no wonder the tailpipes hanging from the second-story ceiling looked to me like grotesque arms and legs, silver, ghostlike appendages stiffened from years of neglect. The older ones were covered with a thick layer of dark brown dust. I could only look quickly and then turn and run away, pounding down the rickety wooden stairs, my brother making bogeyman noises behind me.

Then we’d both get a lecture from my father about making noise in a place of business, and I’d have to be a lady for a little while and sit in Alice’s office while she crunched her numbers on the ancient adding machine that got stuck all the time. I thought Alice was beautiful, like Elizabeth Taylor, but when I’d tell her that, she’d only laugh and hug me. She smelled like Yardley soap.

I watched the dogs eat their peas and, in my six-year-old mind thought all dogs ate peas.

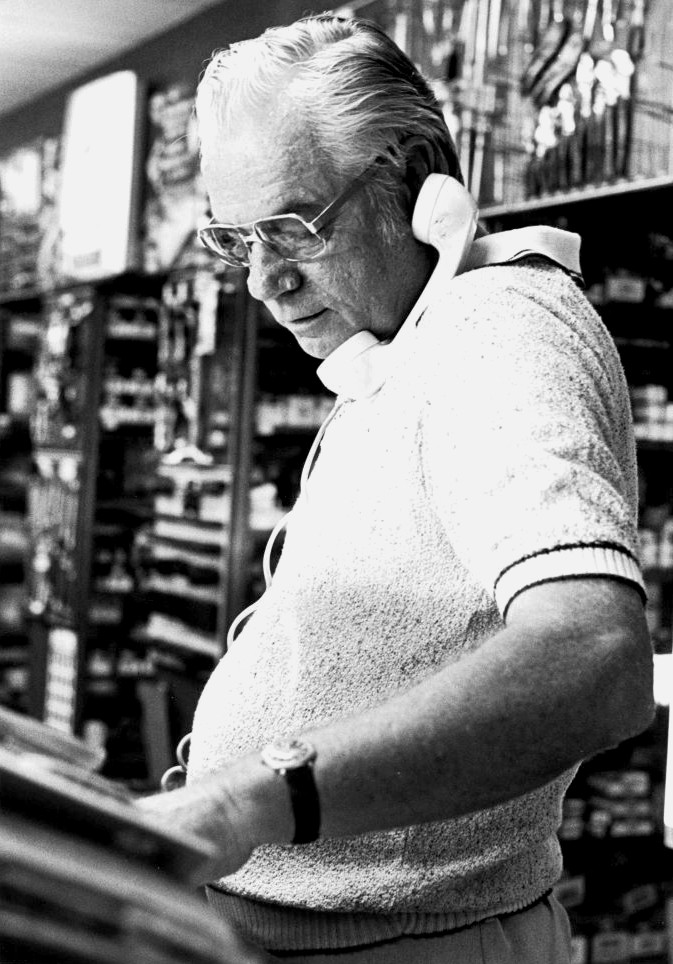

Although it couldn’t have been more than an hour or so, it always seemed like eternity while waiting for my schoolteacher-mother to pick me up. A cigar box filled with stubby Crayolas kept me occupied for a while, but when boredom set in, as it always did, I’d sneak out to the front to hang on one of my daddy’s long arms and watch Mr. Steussy roll a cigarette. His knotted fingers would move so slowly I’d think he’d forgotten what he was doing. Sometimes he wouldn’t even smoke it.

I couldn’t understand why Mr. Steussy and the other old men would want to come to this place. They didn’t say much, and they certainly didn’t do much, except grunt, spit, lean on the chipped and greasy counter, and eavesdrop on customers’ gossipy conversations.

When I was feeling really brave, I’d skip in and out through the aisles of fan belts, spark plugs, headlights, carburetors and air filters, back to the dark, dirty brick wall, inhaling deeply that musty, rubbery smell. There, inevitably, the monster once again waited for his innocent and unsuspecting little sister. Once again, away I’d go to Alice’s office and the safety of my Crayolas.

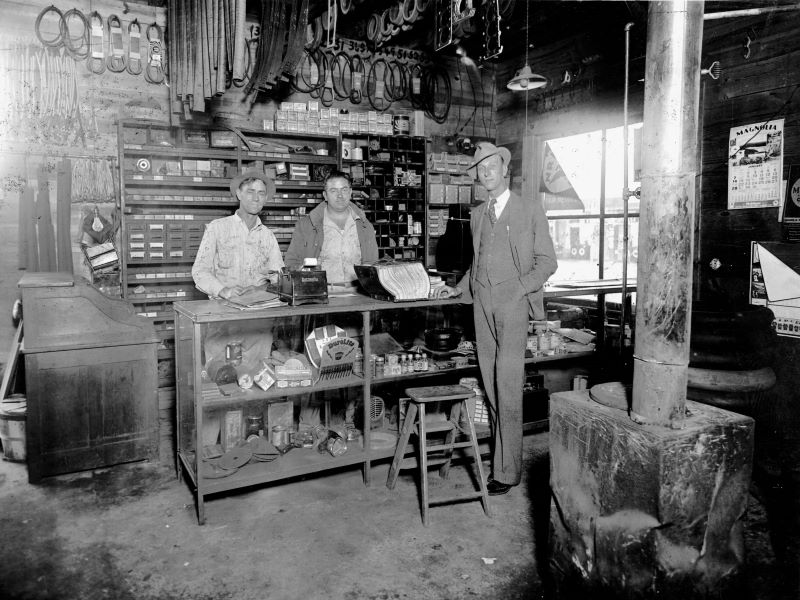

My grandfather and his partner opened the doors of the store in 1929 with less than two dollars between them. My father—my grandfather’s son-in-law—went to work for him twenty years later, once the war had ended and he’d married my mother. The building, one of the first turn-of-the-century hotels in Conroe, was on the north end of Main Street, close to San Jacinto Motors and across from Buck’s Garage, owned by an honest-to-God Native American, the only one I’d ever seen outside the movies.

All the things that made Conroe a typical little East Texas town were within a short walk from the store: the Montgomery County Courthouse, the Crighton Theater, Beall’s Department Store and the Texan Café. The First Methodist Church sat directly behind Quinn’s Drug Store, owned by my Uncle Charles. A twenty-five-cent Coke was just a quick slip away after church, out the door of the kitchen, across the alley and through the back, where often my aunt would greet my brother and me.

When I was a little older, I spent Saturday afternoons at the Crighton, with its exotic, Egyptian-like decor. Lisa and I would sustain ourselves with Dr. Peppers, Milk Duds, and sour pickles, eagerly watching to see who was with whom, who was making out in the balcony, and who had snuck in through the back door. The movie was irrelevant.

Lisa was my best friend; she lived close enough to downtown that we could walk to her house after the movie, taking our time winding through neighborhoods, protected by an unspoken guarantee of small-town safety.

One Saturday there was a partial solar eclipse. Lisa’s mother made a special pinhole card so we could see its effects safely. I didn’t want to look though. The idea of a solar eclipse was too foreign, too far removed from what I knew to be safe and solid.

But I didn’t know about solar eclipses yet in 1959 when I was just beginning to understand my world. I was six years old, in my first year of school, in my first year of spending my late afternoons waiting for my mother in our family’s place of business. Finally she’d arrive to scoop me up, and away we’d go, home to make a meatloaf-style supper and do homework at the kitchen table.

“As much as I hate to admit it, I know that my big brother was right: there are ghosts upstairs.”

My only chore was to feed Rosie and Princess their table-scrap meal in a green ceramic bowl. I’d sit on the back step, my elbows on my knees, my palms on my chin, watching the boxers wag their stubby tails and eat their leftovers in the humid, tree-frog night, the mosquitoes buzzing around my ears. We usually had peas of some kind with supper—black-eyed, purple-hull, or cream peas, mostly—from my grandfather’s summer garden.

I watched the dogs eat their peas and, in my six-year-old mind thought all dogs ate peas.

We’d have other vegetables that had been grown in the garden too, like corn, tomatoes, squash, and turnip greens. But the peas were always the most important thing. My cousins and I fought over my grandmother’s pot liquor, that wonderful pea juice saved from the pressure cooker, to pour over our buttered corn bread, the staple of our lives.

My grandmother made her corn bread as she made almost everything she cooked—without a recipe, without any tools of measurement except a cupped hand and a keen sense of touch. Sometimes, on still, cool nights, I would sit quietly and watch my grandfather eat a simple supper of corn bread soaked in buttermilk in the kitchen of their white-frame house in the piney woods, close to Willis but miles and miles from the rest of the world.

My grandparents were the only babysitters I ever had for the few times when my parents had something else to do. The earthy-smelling well water splashed into the tub for my nighttime bath, and the giant block of Ivory soap, the only soap my grandmother would buy, never sank to make a mushy mess on the bottom of the tub. In the morning, my grandmother would wake me and guide me to the kitchen table where made-from-scratch biscuits and a jar of thick honey awaited.

I caught my first fish within a minute or two after my cork hit the water. I thought it was magic.

If I were lucky enough to be there in late spring, she’d button me up in one of my grandfather’s khaki shirts, tuck my jeans down inside my socks, cover my hands with one of her dozens of pairs of garden gloves, slap a straw hat on my head so the sun wouldn’t get into my eyes, and lead me through the woods to her favorite blackberry vines, constantly admonishing me to “watch out for snakes,” or “stay away from that bull nettle.”

When our buckets were full, we’d return to the house and its cool, attic-fan breezes. I’d wait patiently for my bowl filled with hot blackberry cobbler and watch my grandfather play solitaire on the olive-green, vinyl couch, the worn Bicycle playing cards laid out carefully on the rough, unpainted lapboard carved by hand in his workshop.

Sometimes my grandfather and I would fish in one of the cow ponds, not ever catching much but not ever worrying about it too much either. Mostly though, we fished at our lake, the lake my grandfather and his partner dug out of farmland off Longmire Road in 1948; the lake where I learned to fish with my father as an able and willing instructor, using a cane pole so long I could barely hold it up over the water. I caught my first fish within a minute or two after my cork hit the water. I thought it was magic.

We went to the lake—all twenty-plus melting-pot relatives—because it was Memorial Day, because it was Easter, because it was summer, because it was the Fourth of July and we had to shoot our Roman candles and swing our sparklers outside the city limits, and because it was a safe and compromising ground on which sisters and brothers and husbands and other in-laws could meet and talk and be a family.

The old cabin saw a lot of birthdays, weddings, slumber parties, farewells, and hellos. My brother had a party there when he came home from Vietnam. My twenty-seven-year-old cousin shared many hours there with his friends and his family, knowing he was dying of cancer.

One of the last big family get-togethers at the lake was for my grandfather’s ninety-third birthday, one year before he died, two years before the never-failing, solid rock that held us all together—the store—was suddenly gone.

The store had supported us, sustained us, financed us, employed us, educated us, and made the American Dream come true for my family. When my father took it over in the late 1960s, Houston’s oil-based economy was booming, and we eagerly rode the wave through the ’70s as the solid rock I’d come to know and trust continued to prosper. We moved out of downtown into a modern, metallic structure, a new-and-improved version of what we had. And for a while the ghosts were banished.

No one could have known it would end. No one could have prepared for the shock wave effects the end would have on all of us. All the myriad of people, things, feelings, and memories we shared as a family, the world as we knew it, and the security that told us everything was right with the world was centered on the store.

Its sudden closing was the closing of my childhood, the slamming shut of a way of life I had refused to give up and the realization that my father, however smart he was, did not have all the answers to the world’s problems, including mine.

I never considered while I was growing up that anything would shake the strength that supported us all so well and so faithfully. But it did.

My grandparents, whose light had shone on us all, were gone, their house passed on to my cousin, their treasures divided among grandchildren anxious to save a piece of their memories.

As much as I hate to admit it, I know that my big brother was right: there are ghosts upstairs.

Along with the rest of my world, the small town I called my own, my birthplace, was changing dramatically. Conroe became a mini city, no longer willing or able to guarantee the safety, prosperity, and contentment of its citizens. Downtown as I knew it slowly evaporated, its heart chipped away by progress, leaving only storefront shells and darkened pool halls. Fingers of new growth popped up alongside freshly blacktopped roads, widened and renamed to more closely match the town’s new image, “Houston’s Playground.”

Our lake remains the lone reminder of the life we held so tenuously. It sits mostly unused, quiet and somewhat overgrown, waiting for a buyer.* Occasional fishing trips and quick picnic lunches were all any of us could bear for several years; memories echoed across the still water on empty Sunday afternoons, pleasant yet painful, welcomed yet dreaded.

Money, something we had regarded as a useful but powerless resource that we controlled and shared quite generously with one another, suddenly became an evil villain bent on proving that it, not love, was the thin glue that had us together all those years.

From the Sunday in January 1987, my father’s birthday, when we closed the doors of the store for the last time, I began a slow journey away. I moved erratically through periods of grief, just as if a beloved member of the family had been taken from us. I was angry, bitter, depressed, and frightened. I worried about my parents. I worried about my brother. I wondered what people would think.

Then one day I said the word out loud. Bankruptcy. I was inching my way toward hope, away from despair. If I could accept it, if I could talk about it, maybe we could all make it through this. Maybe things could be okay again. But it was certain that nothing could ever be the same.

I’d replaced the childlike trust and sense of fairness that guarded my world of long ago with caution, uncertainty, and a heavy dose of cynicism. I know that nothing is forever, nothing is safe, and nothing is sacred. And although I don’t believe I can ever achieve it, the overriding goal of my working life has become obsessively focused on building financial security.

As much as I hate to admit it, I know that my big brother was right: there are ghosts upstairs. They rattle their chains. They wail and scream. Sometimes I don’t listen; sometimes I want to run away and pound my feet down the rickety wooden stairs. But the ghosts of my childhood still follow me. And in many ways, they are far more frightening.

*This story was previously published in The Houston Chronicle, “Texas Magazine” Supplement, June 9, 1996. The lake property referred to in this story was sold in 1999, just one month following my father’s death.

2 thoughts on “Even Rocks Crumble”

Excellent Chris. Just excellent. Love how your descriptions of childhood memories immediately evoke similar images and events from my own life.

Chris – Simply amazing! I was thrilled to come across your story and the associated pictures! My grandfather, Otis Ross Ferguson, son of Vernie Hazel, was named after your grandfather, Vernie’s brother, Otis. I can’t tell you the value your writing brings to me! Thanks SO much for sharing!