When you grow up within a large multigenerational extended family, it can be extraordinarily confusing to decipher which second and third cousins belong to which branches of the gigantic family tree. For me, the annual family reunions were massive jigsaw puzzles of faces and names that seemed to grow immeasurably each year, whether blood-related or otherwise.

Amid those who belonged by right of DNA and those who were obligated to be there by marriage, there were also those welcomed hangers-on who unfailingly showed up and remained in the shadows, encouraged by many to enjoy their share of baked ham or fried chicken, corn on the cob, turnip greens, homegrown tomatoes, cornbread, pound cake, and sweetened iced tea before silently making their exit.

Roy was one of those—a nearly invisible extra in the ongoing storyline of the family, content to peek in from the sidelines and disappear behind the curtain when the whole conglomeration reached an apex—but only after filling his own containers with the various trappings of the potluck family meal. He would slip away almost unnoticed to his tiny white house nearby to enjoy several days’ worth of homemade meals in peace. We all wanted him to stay. It just wasn’t within his capability to linger and chat, reminisce, exclaim over someone’s newest grandchild, or get caught up on all the extended family’s comings and goings.

“Family is not blood-bound. Family is not only the people we are linked to by birth, circumstances or documentation. It is the people we encounter along the way and hold tight in our hearts, for whatever reason, no matter how unlikely or unforeseen that bond may be.”

Through the years, I occasionally thought of Roy and wondered about his story. There had to be far more than what I thought I had known, more of a real story than what my research into our family tree later documented. Roy was joined to the clan twice through two different marriages—his sister’s marriage to one of my grandmother’s brothers, and his father’s second marriage to one of my grandmother’s sisters. Then I discovered several well-preserved black-and-white negatives of Roy from the early 1950s that showed a side of him I’d never imagined, but it also opened up a whole new pile of questions. Who were you, Roy, and what had happened to you?

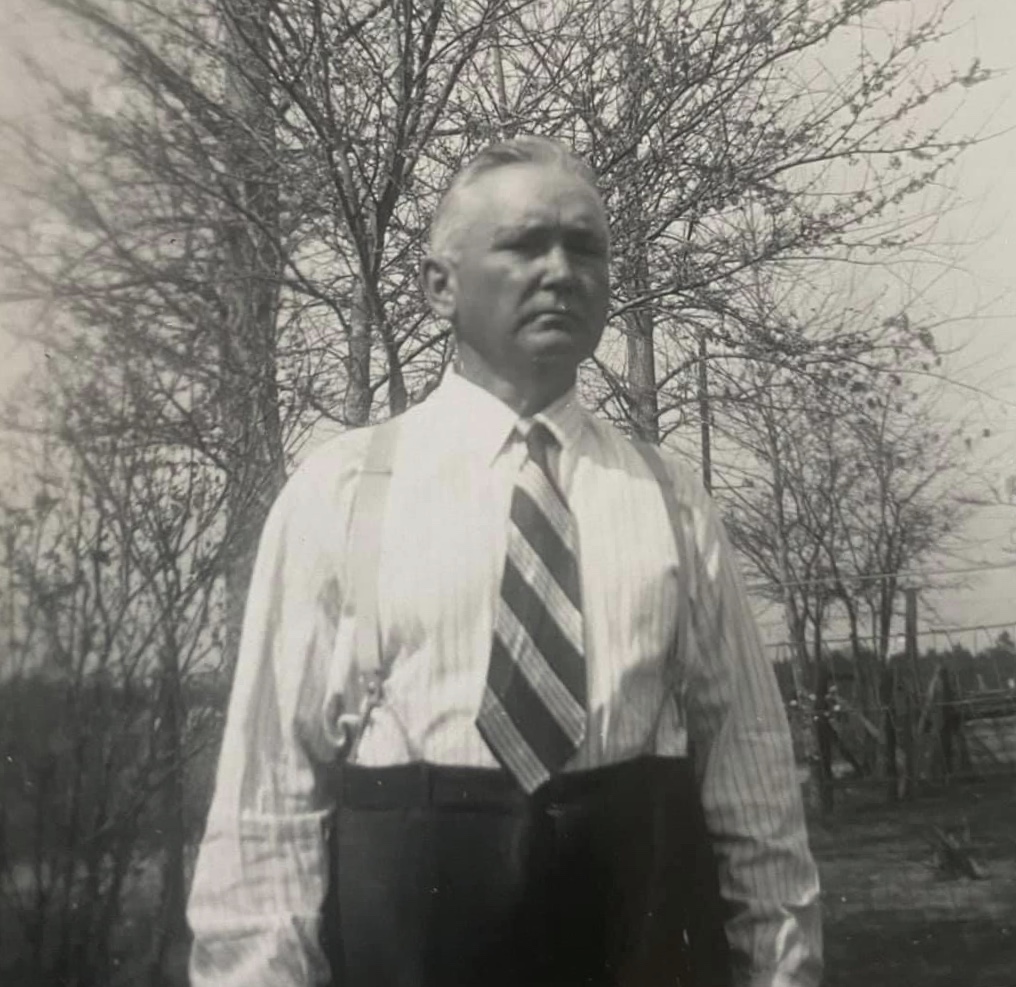

Roy served his country during World War I but returned a changed man. When the photos were taken—before I was even born—he had just been released from a psychiatric hospital after decades of treatment. The photos captured that homecoming. He proudly sported his brand-new suit, standing fresh-faced with his sister by his side in one shot, with his young nephew and a half sister in others and in yet one—alone—looking in all of them like the proverbial polished salesman, the adept professor, the inspiring Baptist preacher, the upstanding member of any community in any town in this country.

In harsh reality, however, Roy was a loner, more at home with his suspenders and his jungle hat, his wire-rimmed glasses and unassuming round face. He was, by all accounts of those in the family who did know him, an extremely nice man, but sadly damaged by whatever it was that made him forever fearful, that scarred him for the rest of his life and kept him so alone. I cannot possibly imagine what torment he must have felt. Not all of us are suited for battle, for devastation, for trauma.

In 1970, my grandmother drove me the short distance from her house to Roy’s playhouse-like cottage, all on the family land that once belonged to my great grandparents. Roy’s house was simple, compact, yet immaculate. My mission was to sell Roy a magazine subscription, one of countless I’d already sold as part of the annual fund-raising drive for the high school’s junior class.

My grandmother was quite efficient—but friendly and caring—as she explained why we had unexpectedly come to call. I had no idea at the time, of course, that all this had been prearranged to avoid any undue angst or anxiety on Roy’s part by giving him ample time to prepare for my visit. I quietly made my pitch, and to my surprise, Roy said he’d just realized that he needed to renew his subscription to TV Guide. It was a quick transaction, and we left him in peace.

Roy grew bountiful vegetables year after year in a garden far larger than his house, occasionally allowed check-in visits from yet another of my grandmother’s sisters and yes, shuffled in and out at the annual family reunions. Basically, he lived out his uneventful life in relative obscurity.

Some might argue that without a blood connection to the family, Roy had no legal claim to the spot of land he occupied nor the cottage he happily lived in for several decades. But it was the kindness of his blended, connected family that brought him home, that clothed him, housed him and cared for him as best they could—without reservation. Through the gift of that precious human connection filled with compassion and generosity, Roy was rooted—rightfully—where he belonged.

In the photos from his homecoming day, I see such hope in his face—a steadfast grip on reality, a resolute step toward some semblance of normal. He had a place, a home, a family around him, and a quiet future of solitary reflection in his tiny space in a giant world.

No one ever spoke openly of what precisely troubled Roy—no clinical diagnosis specific to him was ever widely shared, although I suspect it was similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, otherwise known in Roy’s military days as “shell shock.” In my family, however, I am not sure it even mattered. My mother, a veteran of World War II, made it quite clear that he was to be treated with respect and dignity and per his desire… distance.

I can relate to Roy’s need for space, for solitude and aloneness, but perhaps it was my own penchant for distance that prevented me from knowing him, combined with a generational difference and a psychological barrier that made most human connections difficult for him. But Roy’s rediscovered story is not his alone.

Family is not blood-bound. Family is not only the people we are linked to by birth, circumstances or documentation. It is the people we encounter along the way and hold tight in our hearts, for whatever reason, no matter how unlikely or unforeseen that bond may be. With these rare and precious gifts, there is no expectation for anything other than doing the best we can, no matter the difficulties, no matter the differences, to take care of one another—just like family.

Thank you, Roy, for your service to your country and for your unobtrusive yet meaningful presence within our family story. May you rest in peace… and quiet.

*Feature photo is of Roy and his half-sister, Verna

3 thoughts on “The Potluck Life of Roy”

What a lovely recollection – beautifully told!

Brings back long ago memories of the “Roys” in my past. Splendid composition.

Wonderful story with great understanding